The Importance of Sequence

Data analysis in audits focuses primarily on values. Think of amounts, quantities, balances, ratios, but also outliers in invoices or reconciliations between sub-ledgers and the general ledger. The core question is usually: is this amount logical? or does this value deviate from the rest?

Process mining asks a different question. Not what has been recorded, but in what order things happened. It looks at the flow of transactions through a process. For example: is a purchase order always approved before receipt? Is payment sometimes made before an invoice is registered? And how often does the actual process deviate from the formal procedure?

This shifts the focus from individual transactions to process behavior over time. That makes process mining fundamentally different from many other audit analyses.

What is an Event Log?

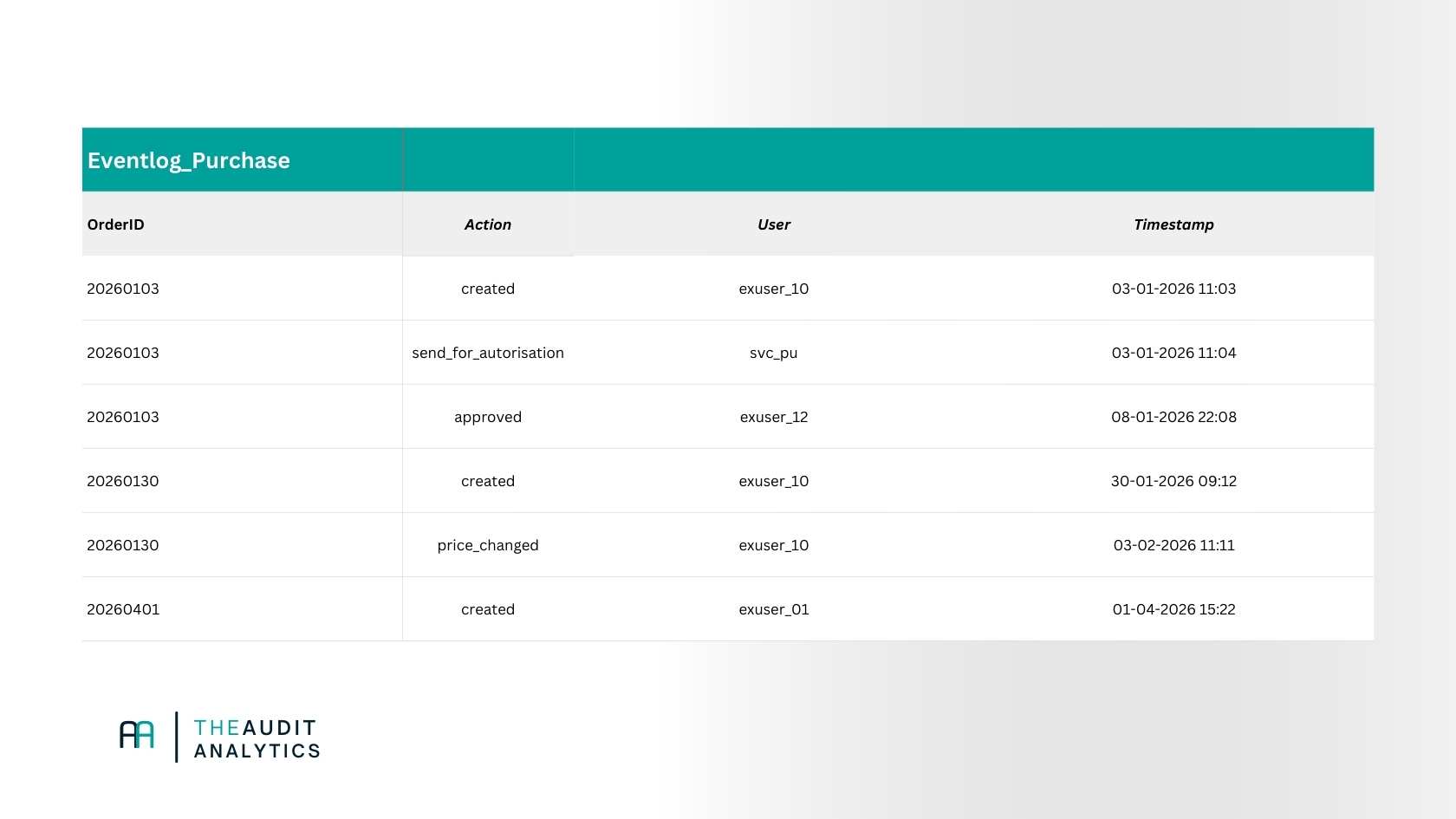

The basis of process mining is the event log. This is simply a structured table in which events are recorded. Every event log essentially contains three elements.

First, there is a case ID. This is the object the process revolves around, for example, an invoice number, order number, or file ID. Everything that belongs together must have the same case ID.

Second, there is the activity. This describes what happens: “invoice received”, “approval given”, “payment executed”, etc.

Finally, there is a timestamp. This records when that activity took place. Without time, there is no sequence, and without sequence, no process mining.

In the example above, a user is also added; this can be very useful (to find out who did what, provided GITCs allow this), but it is not necessary to understand the process at its core.

In theory, this all sounds quite clear. In practice, this event log often turns out to be the bottleneck.

Challenges

Many process mining initiatives fail not because of the tool, but because of the data and expectations.

A first problem is incomplete logging. Not every process step is recorded in systems. Approvals sometimes take place verbally, via email, or outside the ERP. The event log then shows a seemingly deviating process, while the control actually did take place. For the audit, this is risky: you see a deviation, but you don't know if it's real.

In addition, there are often too many variants. In theory, there is one standard process. In the data, there turn out to be hundreds or thousands of variants. Small timing differences, extra steps, exceptions, and manual corrections cause a so-called "spaghetti process". Visually impressive, but analytically difficult to interpret. Which variants are normal, and which are truly deviating?

Example of a Spaghetti process (via Researchgate)

A third pitfall is that process mining often results in (beautiful) visualizations without hard audit evidence. A process diagram shows that something happens, but not automatically if it is allowed. The step from process observation to audit conclusion is bigger than often thought. Without a clear norm, tolerance, and link to risks, it remains an illustration.

What Process Mining Can Mean for Auditors

Process mining is primarily an exploratory technique. It helps to understand processes as they actually run, rather than as they are described on paper. This can be very handy in the planning phase of an audit, in identifying process risks, or in substantiating where exceptions occur structurally.

Applications

A common application of process mining is testing the sequence of a number of important steps. Think of the question whether an invoice was actually approved before it was booked or paid. In the analysis, you only look at a few events, such as receipt, approval, and payment. Process mining quickly reveals if this sequence structurally deviates for a portion of the transactions.

Time patterns are also relevant in practice. For instance, you can signal if steps follow each other unusually quickly, while a manual check normally takes place there, or if there is an extremely long time in between. This does not yield proof, but it does provide indications for possible circumvention or process problems.

The power of process mining in audits therefore lies not so much in broad or deep analyses, but in small, focused applications that can help determine where further control is needed.